The Merz’s and the Willow Place Houses

The Merz’s

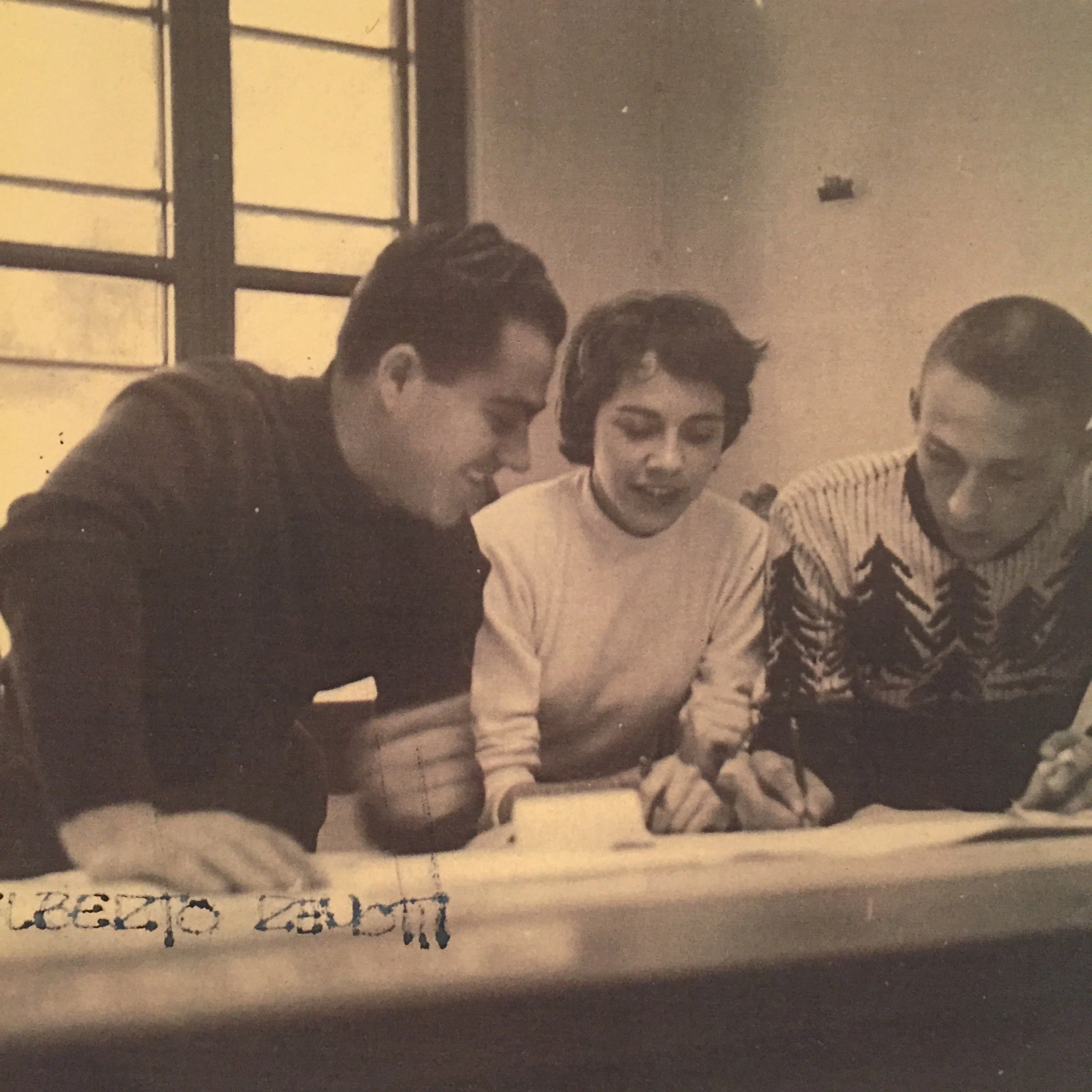

Mary and Joe Merz were a husband-and-wife architectural team based in Brooklyn Heights. Joe Merz, born in 1928, studied architecture at Pratt Institute and briefly at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, working early in his career with architects such as José Sert and Morris Lapidus. Mary Merz (née Linberger) also studied at Pratt, where they met; she later received a fellowship to study Renaissance art in Florence and worked at Edward Larrabee Barnes Associates before forming a practice with Joe. They married in 1957 and founded Merz Architects soon after, working together for decades.

Their architecture is rooted in mid-century modernism, marked by clarity of structure, careful proportion, and sensitivity to materials and context. They are best known for a trio of modernist townhouses on Willow Place in Brooklyn Heights, designed in the 1960s, including their own home and studio. These buildings, using concrete block, redwood, and restrained detailing, stand out for introducing modern design into a historic neighborhood without overwhelming its scale or rhythm.

Merz Architects received recognition from the American Institute of Architects for residential and civic projects that balanced modern innovation with human scale. In addition to private homes, they completed institutional and federal work, including office interiors, university projects, and accessibility renovations at national monuments such as the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, demonstrating a broad and socially engaged practice.

Mary and Joe Merz were deeply involved in urban advocacy and preservation in Brooklyn. They opposed destructive urban renewal schemes, supported community-driven planning, and contributed to local playground, garden, and public-space initiatives. In the 1970s, they served jointly as curators of Prospect Park, promoting a philosophy of minimal intervention and respect for the park’s natural and historic character.

Mary Merz died in 2011 and Joe Merz in 2020, but their work remains a touchstone for discussions about modern architecture in historic urban contexts. Their Willow Place houses are widely regarded as exemplary models of how modernism can coexist with preservation, and their broader legacy reflects a life-long commitment to architecture as a civic, cultural, and community-centered practice.

Willow Place and the Three Merz Houses

Willow Place is a short, tucked-away street in Brooklyn Heights, part of what’s often called Willowtown. By the early 1960s, several buildings on the block had been torn down and the lots were sitting empty — scars left by city clearances and unrealized redevelopment plans.

In 1961, architects Joe and Mary Merz bought three of those vacant lots at a New York City auction. They weren’t developers looking to maximize square footage. They were architects who lived in the neighborhood, believed in it, and wanted to prove that new architecture could belong in a historic place without overpowering it.

Over the next several years — mid-1960s into the late ’60s — they designed and built three modern townhouses at 40, 44, and 48 Willow Place. Each house was different, each designed for a specific person or family, but together they formed a quiet, intentional group.

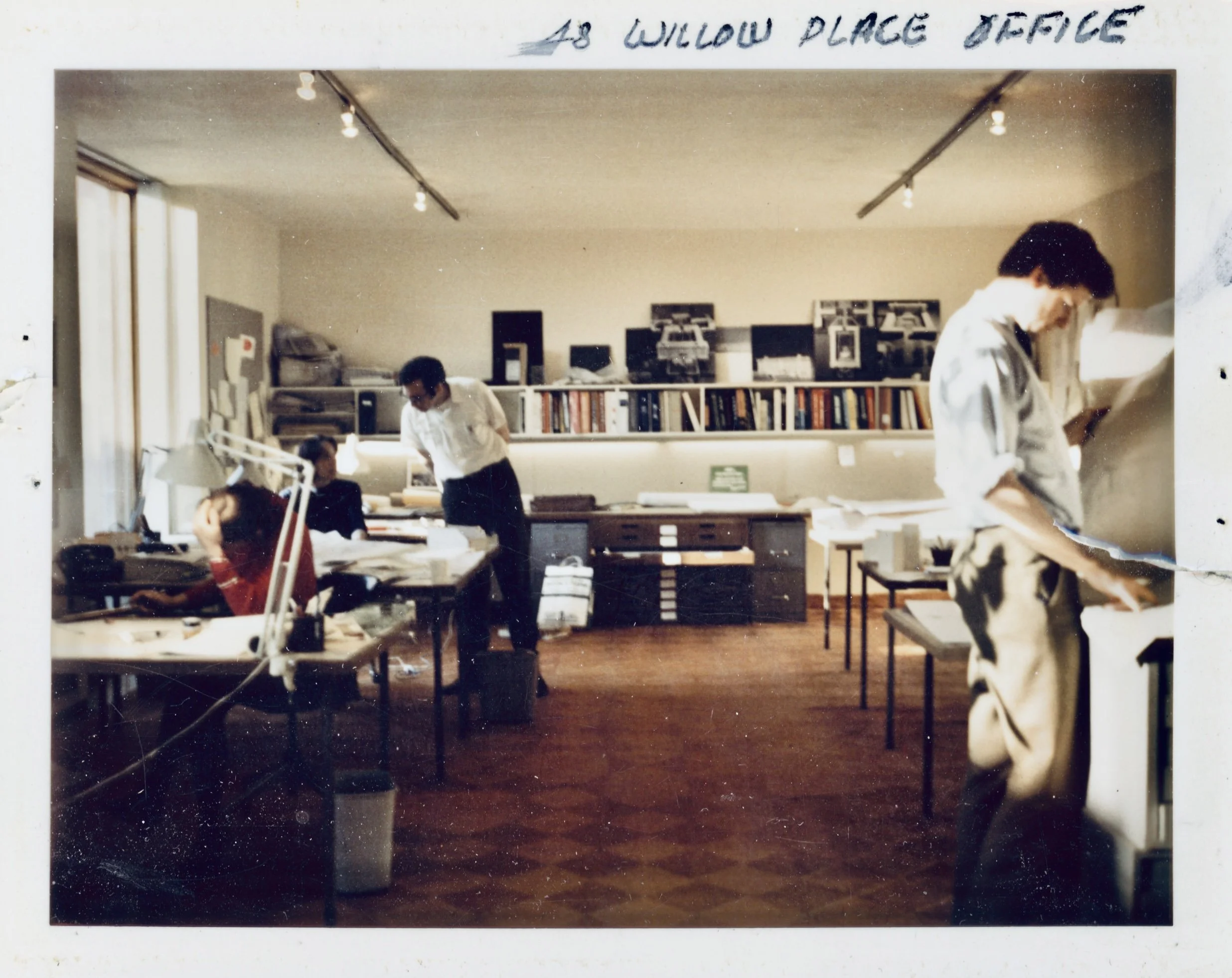

48 Willow Place was the heart of it all. Joe and Mary built it as their own family home, and it also became the office for Merz Architects. It was a place where living, working, drawing, and thinking about the city all happened under one roof.

40 Willow Place, the largest of the three, was built on two combined lots and commissioned by Leonard Garment, a lawyer, art supporter, and longtime Brooklyn Heights resident. This house helped establish the project’s reputation and went on to receive architectural awards.

44 Willow Place was designed for Ron Clyne, a graphic designer, and his wife Hortense. It is the most understated of the three, calm and precise, but just as intentional.

At the time, building modern houses in a historic district was not a given. These homes were carefully reviewed and approved, and they remain among the only modern residences ever allowed in the Brooklyn Heights Historic District. Their success helped show that preservation didn’t mean freezing a neighborhood in time — it meant caring deeply about scale, proportion, and continuity.

Today, the three Merz houses are seen as a rare moment when new architecture was added with humility, intelligence, and love for place. They aren’t loud. They don’t imitate the past. They simply belong.